Phenomenally Imperfect…

Why We All Want Weird Gems

The one consistent theme of 2023? Everything is getting weirder.

I’ve written about gemstone and diamond trends before, predicting the popularity of portrait cuts and east-west settings for Rapaport in March 2020.

An especially interesting trend is emerging that feels so left-field, it’s worthy of further exploration…

We’ve witnessed a shift that has seen gemstone purchasing increasingly driven by spirituality and even mysticism - from birthstones to belief in healing properties - and this is part of the ongoing evolution of the public’s relationship with gemstones.

Those purchasing gemstones are rejecting conventional motivations (e.g. the popularity of old cut diamonds vs. optimal faceting and brilliance in modern cuts, the affordability of large lab grown diamonds satisfying desires for larger stones etc.,) and are searching for unique gems which allow deeper, much more personal connections with the wearer.

“Quartz with a star-like actinolite inclusions.” Via @giagrams

Gem Phenomena

It’s no wonder then, that the weird and wonderful accidents of nature which create gemstone phenomena are beginning to appeal: the GIA (Gemmological Institute of America) shares images and details of exceptional gems of all types, from giant uncut diamonds to strange specimens that defy belief.

The latter category ranges from unusually shaped inclusions in rock crystal to parasitic gem formations - these extraordinary features result in gems whose appearance is diametrically opposed to the engineered perfection of brilliant diamonds. It is these ‘imperfections’ that are being newly appreciated for their unconventional beauty.

While these examples are typically museum-grade gems, the psychology that attracts us to these pieces trickles down into real consumer behaviour...

An accessible version of this weird gem trend: “quartz with lots of lepidocrocite inclusions by @talkative_marotta.” Seen via Annabel Davidson.

Quartz with bent rutile inclusion via @giagrams

Behind carat weight, clarity is generally the determining factor in the cost of gems (considering the 4C’s, it’s arguable that colour grading is becoming less important, as personal preference for colour gradually takes precedence over formal rules of ‘best’ tones.)

‘Salt and pepper’ (meaning ‘heavily included’) diamonds were marketed as an affordable engagement ring option in the late 2010s, but these generally didn’t showcase unique inclusion patterns, rather the novelty was the grey static appearance that consistent, strongly included diamonds present.

Parasitic Gems

There’s some thing fantastically freaky and supernatural about parasitic gemstones. They’re truly alien in the sense of their otherworldliness: their appearance at once bringing to mind their ancient origins, as well as fantastical renderings of retro futuristic space, or digitally rendered gems in gameplay.

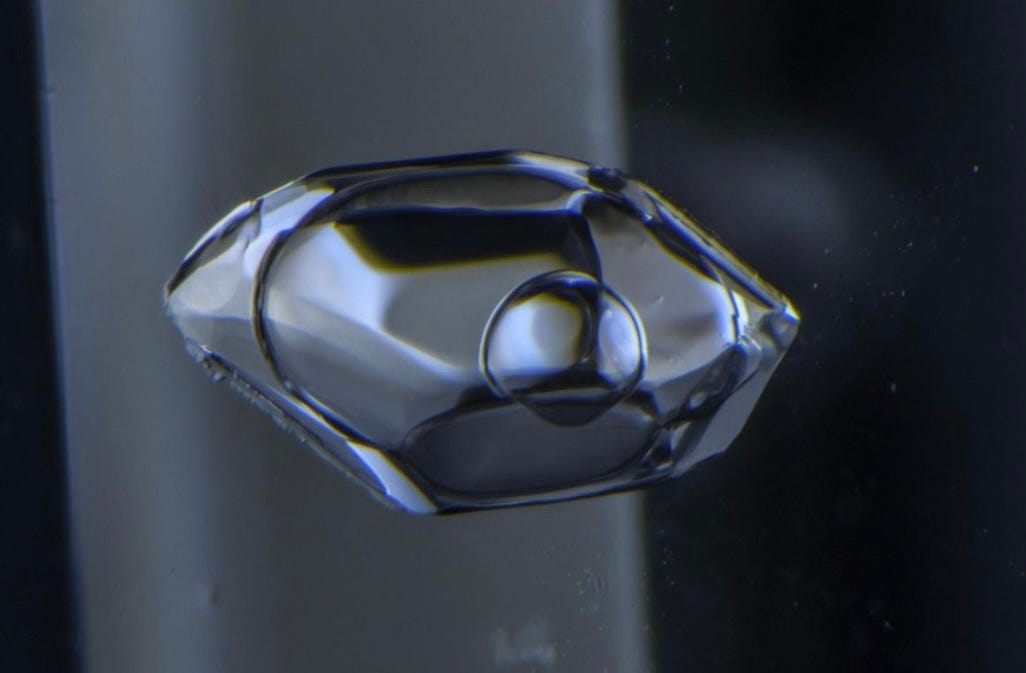

Whether it’s diamond, quartz, aquamarine or any other gem, these natural phenomenons are essentially a smaller gemstone which has grown inside larger gemstone ‘host’, and remains encased inside.

Via Jean-Noel Soni of @topnotchfaceting

Here, the spectacle of seeing the inner world of the gemstone is part of the appeal, though in a deeper sense, these types of rare gems connect the observer to the fundamental appeal of gems - that these are wonders of nature.

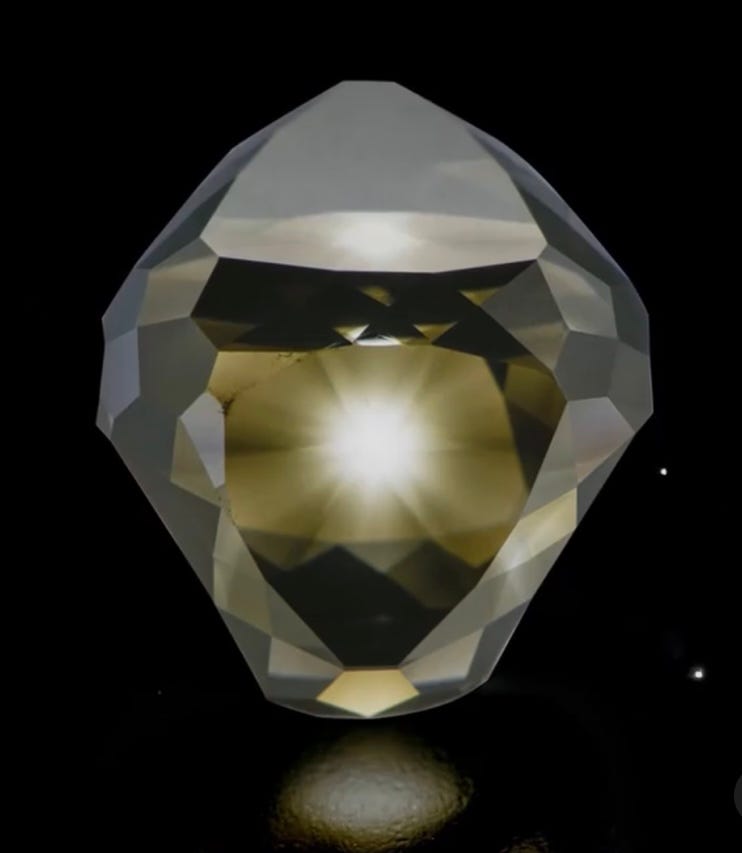

“20.59ct topaz from Gilgit-Balistan, Pakistan.” via @giagrams

Basically, throw the conventions out of the window.

The weirdos are taking over everything, and that includes diamonds and gemstones.

![1 OF 1 magazine [Jodie Smith]'s avatar](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!nyBC!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa99203f7-0cbb-407f-ab1a-3cf0a14be44b_2435x2435.jpeg)